Original: August 2018

Updated: April 2022

Blood samples are a critical component of anti-doping programs because they allow laboratories to detect prohibited substances and methods that are not detectable in urine samples. However, athletes who have experienced traditional blood collection know that taking blood samples from a vein in the arm (also called venipuncture) can be invasive and sometimes painful. This process also requires a skilled blood collection officer with phlebotomy training and the expense of rapid, cold-chain shipping to the laboratory.

Until now, venipuncture has long been the only reliable and feasible blood draw method available, but thanks to new medical device technology, that may now be changing. As the healthcare industry introduces technologies that allow for quick, painless, and at-home blood draws, USADA and anti-doping experts around the world have also been conducting research that would combine these athlete-friendly and cost-effective collection technologies with a reliable sample analysis matrix to better fight doping and improve the athlete experience.

Together, these methods comprise Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing, which USADA has been piloting for a number of years to advance the most effective and reliable blood collection process and equipment for both athletes and clean sport. As DBS is now a WADA-approved method, more athletes should expect to experience DBS collections in the coming months and years as a complement to existing urine and blood collections.

Below is more information about this innovative collection and analysis method:

1. What is DBS?

With DBS, a very small amount of blood can be captured from capillary blood vessels in the skin (rather than a vein), then blotted and dried on paper or other suitable absorbent material (like a polymer). The sample is shipped to a World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)-accredited laboratory, where the blood is processed and analyzed to detect prohibited substances or methods.

2. How can DBS testing advance anti-doping?

While urine testing remains the gold standard in anti-doping, DBS provide a complementary testing method to those already in use, including urine, whole blood, and serum (collected venously via venipuncture). Published research has demonstrated that DBS analysis can detect a wide range of substances and biomarkers, while also enabling easier transport, longer storage of blood samples, and greater opportunities for reanalysis.

Additionally, DBS testing could allow USADA to collect blood samples from more athletes, at less cost, and with greater comfort for the athlete. USADA has also recently successfully piloted DBS for virtual (remote) sample collections via video conferencing platforms.

3. Is capillary blood different from venous blood?

The traditional blood sampling technique, venipuncture, uses blood from a vein, while DBS uses blood from capillaries under the surface of the skin. The composition of the blood is similar, but the way it’s extracted is very different. Collecting venous blood requires a licensed phlebotomist to conduct the procedure, which can also be painful, while capillary blood can be collected painlessly and without the assistance of a blood collection professional. Capillary collections also require far less blood, about 25 times less, at just 0.08 milliliters (mL) compared to venipuncture draws that require 2-5 mL. Additional equipment advancements may allow even greater DBS volumes, enabling the labs to conduct more analysis while still minimizing the amount required from athletes.

4. What kinds of collection devices enable DBS collections?

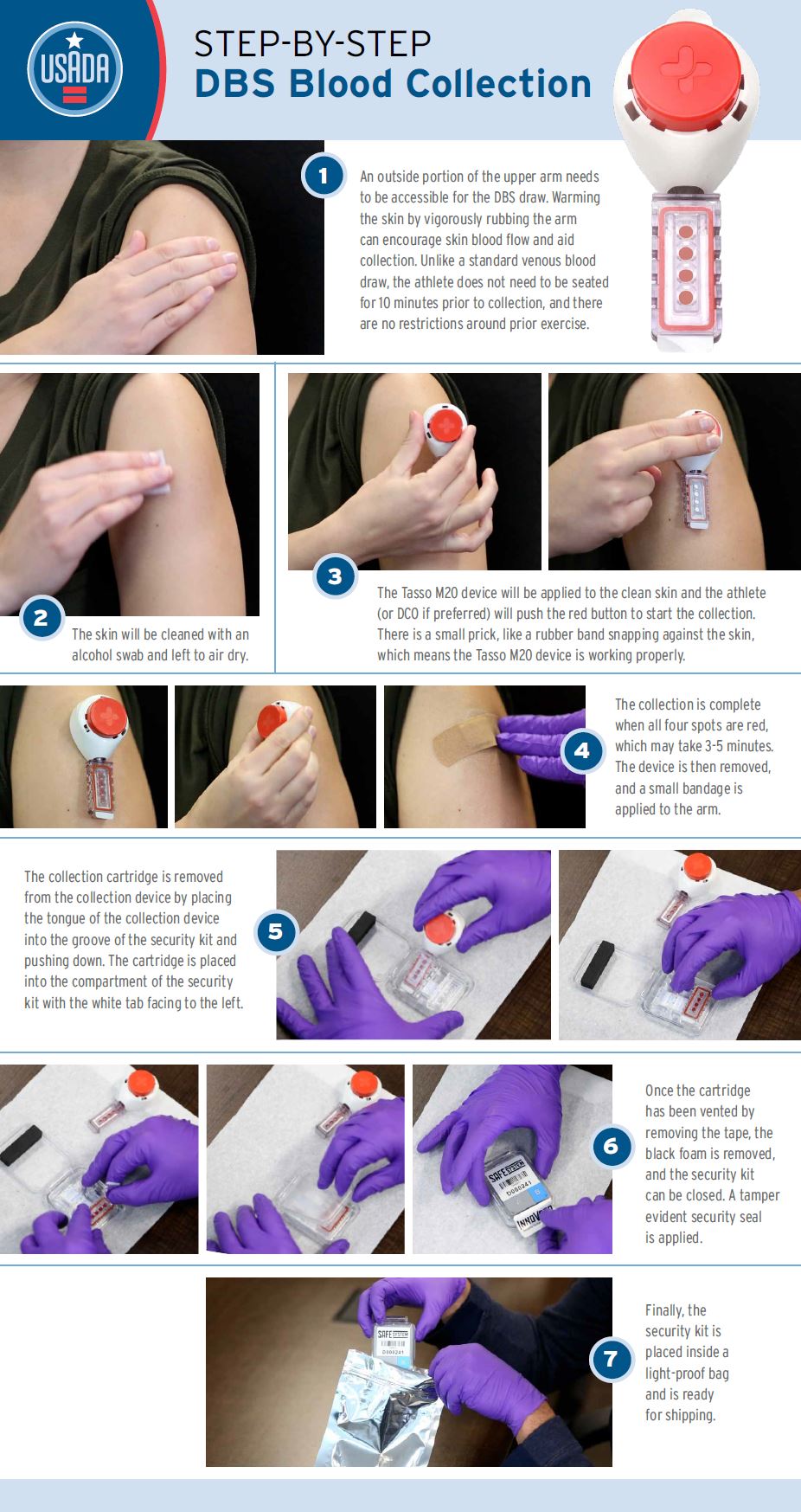

Capillary blood collection devices can draw blood from various surfaces of the body, including a finger, heel, or arm. USADA currently uses FDA-registered devices that collect blood from the upper arm with very little or no pain. Being registered by the FDA and other regulatory bodies for human use means that the safety and efficacy of these medical devices are closely regulated and monitored. USADA currently uses the TASSO M20 device for DBS collections due to the ease of collection, the blood collection and DBS spotting being totally integrated, and the reliability of the device.

5. How does sample collection generally work?

A DBS collection device is pressed onto the arm after warming and secures to the skin with a light adhesive. At the firm press of a button, micro-lancet(s) pricks the surface of the skin forming a very small cut. The blood flows out of the capillaries through the microfluidics of the device and is deposited into a sample pod attached to the device. In general, the collection takes about 1-5 minutes.

If the Tasso device cannot be placed on the arm for any reason, it will be placed on the athlete’s stomach.

6. Are there any side effects?

As with all blood testing, there is a small chance of adverse side effects. For example, an athlete may feel light-headed or nauseous at the sight of blood, or there is a small chance of infection. However, compared to venipuncture, the risks are very minimal. In fact, athletes and sample collection personnel both report that the blood draw experience is vastly improved with DBS collections.

7. Has research been conducted about the application of DBS testing for doping detection?

Dozens of research publications highlight the use of DBS to detect a diverse spectrum of substances prohibited in sport, including anabolic agents, peptide hormones, beta-2 agonists, hormone and metabolic modulators, diuretics and masking agents, stimulants, narcotics, cannabinoids, glucocorticoids, and beta-blockers. As more research is conducted, the number of substances and methods that can be detected with DBS will continue to grow.

8. What are some of the limitations of DBS?

The main limitation to DBS is the relatively small volume of blood, making it necessary to analyze each sample for a finite list of substances. As the blood draw capacity of DBS collection devices improves, it is anticipated that labs will be able to analyze each sample for a larger list of prohibited substances. It is also not possible to analyze a DBS sample for the purposes of the Athlete Biological Passport, therefore DBS cannot fully replace venous blood collections.

9. Is DBS testing a routine collection and analysis method?

USADA collected DBS samples for several years to support its testing, investigations, and scientific efforts. As of September 1, 2021, WADA officially approved the use of DBS samples to identify the use of prohibited substances and it is now a routine collection and analysis method.

USADA has recently collaborated on the development of a DBS security kit optimized for anti-doping collections and transport to the anti-doping laboratories. This latest advancement has greatly assisted the implementation of DBS collections into routine testing in the U.S. and globally.

10. What other research is on-going to improve blood collections and detection of doping?

Research is being conducted in the U.S. and globally to improve the blood collection experience for athletes while upholding the strict standards for anti-doping analysis. While DBS is currently limited to detection of the presence of prohibited substances (but not the amount or concentration of the substance), USADA and others are examining new micro-volumetric blood collection methods (shrinking the volume of a blood sample) to perform analyses for human growth hormone and erythropoietic blood doping agents, as well as improving both direct and indirect detection of blood biomarkers that may be useful for the Athlete Biological Passport. Our vision for the future includes the possibility of moving away from venipuncture blood collections entirely, increasing the number of blood collections conducted, and even establishing virtual blood collections administered by the athlete. As with all anti-doping testing, the impact on the athlete and the effectiveness of detection and deterrence are heavily considered.

CLICK HERE FOR A PDF VERSION OF THE STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS